Underutilized Office Space: Ripe for Reinvention

Restoring the vibrancy of cities through the adaptive reuse of existing buildings to catalyze positive and sustainable change.

By Michael E. Liu AIA NCARB, Principal Emeritus

By now everyone is aware of the public discussion around office to residential conversions as a solution to addressing the eye-watering vacancy rates in downtown office markets brought on by COVID-19. Suddenly an entire nation of office workers realizes that they don’t have to work in an office, which has emptied out city centers everywhere. City officials across the country have embraced the idea of residential reuse to infuse empty office blocks with the 24/7 activity that urban residential uses could bring. In July, Mayor Wu announced a “Downtown Office to residential Conversion Pilot Program” of tax incentives and streamlined permitting for Boston. The next month, Mayor Adams launched a similar program in New York and many other cities are following suit.

Despite the boosterism of public officials, the idea has had a lukewarm reception from the real estate community. In conversation and in articles, there seems to be widespread skepticism of the idea. This is intriguing, given that our firm has converted every conceivable structure to housing. It hasn’t mattered how specific the original building design was to its original purpose, there have always been ways to make the buildings work for housing. We have adapted schools, factories, warehouses, hospitals, streetcar trolly garages, and power plants to housing. Given this, we can collectively rise to the challenge of office conversion.

What seems clear, however, is that the naysayers have a certain kind of office building in mind when they express skepticism about office to residential conversion. They are not talking about early 20th century office buildings such as the 23 story 1920’s era Superman Building which TAT is currently converting to 308 units in Providence, Rhode Island. The obstacles commonly cited suggest they are talking about modern office towers.

The two issues raised most often are the building envelope and the deep floor plates of typical office towers of the fifties through to the present. These challenges seem overstated.

While the skin of a glass office tower is often non operable and, depending on the vintage, not particularly energy efficient, retaining it as is need not be an a priori assumption. Many older glass office towers may need to be reclad anyway and in other cases, sections of curtain wall or stacked storefront exteriors may be selectively replaced with operable sections.

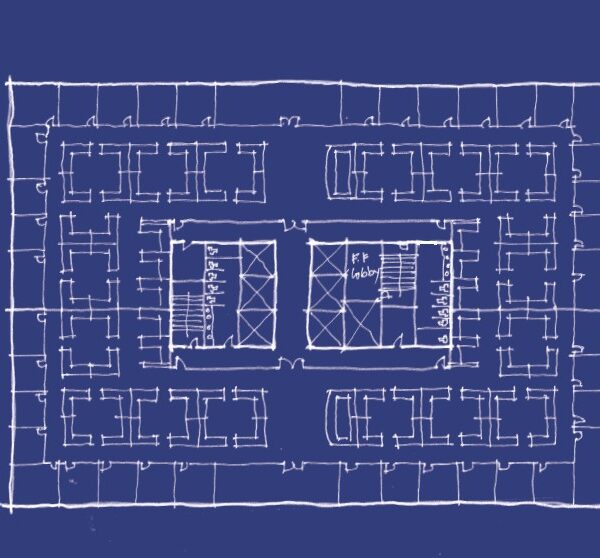

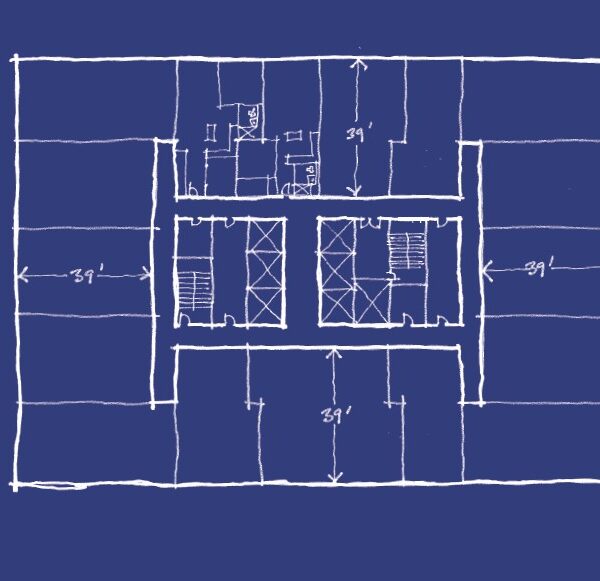

Diagram A

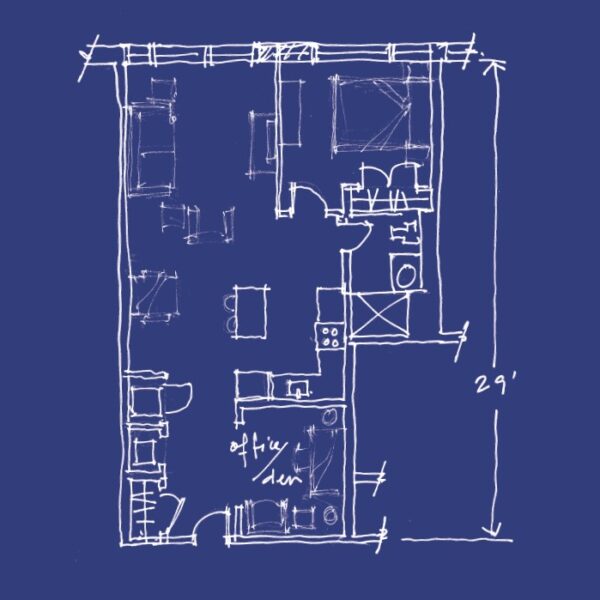

As far as floor plate depth is concerned, the cross-sectional width of the typical office tower may be a market benefit in the work-from-home environment. The generic modern office layout is 45’, 30’, 45’ in cross-section (see diagram A), the 30’ representing the width of the core and 45’ from the core to the exterior wall. In a multi-tenant scheme this makes the distance from the common corridor to the exterior wall 40’. The typical cross-sectional width of a double-loaded residential building is between 60’ and 70’ with the depth of the apartment 28’ to 32’ measured from the common corridor to the exterior wall. That extra 8’ to 12’ of apartment depth then provides enough space for the much sought-after home office, or even a small interior bedroom with borrowed light. Common restrooms in the core can be converted into revenue-generating tenant storage.

Diagram B

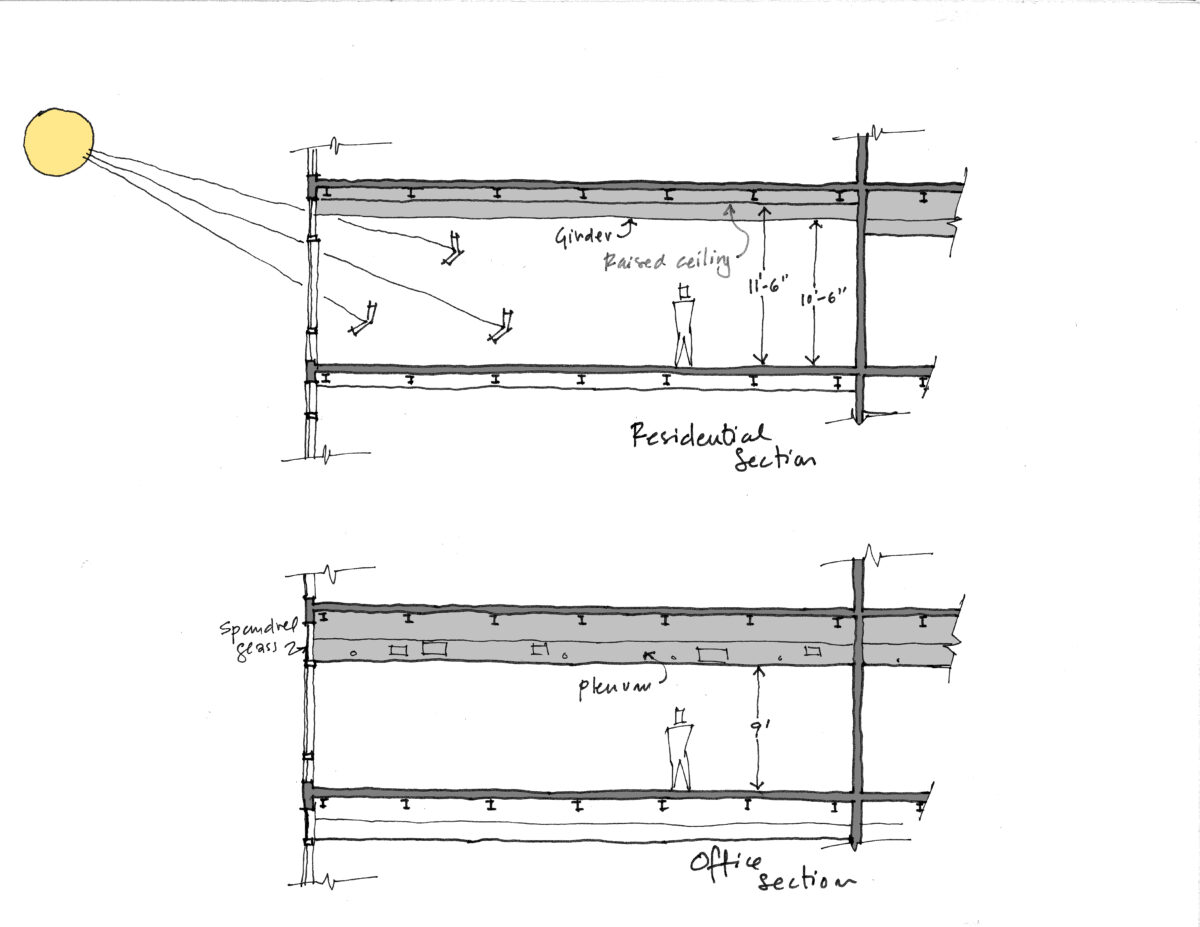

Another benefit of the office structure is the ability to provide much higher ceilings which improves penetration of natural light and offsets the greater unit depth. This is especially true if an all-glass exterior can be maintained. The floor-to-floor height of a typical office building with a VAV HVAC system is usually around 13’ to allow for air distribution above a dropped ceiling at 9’ (see diagram B).

Since residential buildings do not require such extensive air distribution the dropped ceiling could be eliminated or raised to the underside of structure, the lowest sections of which might be almost 10 ½’ above finished floor, or even higher if the ceiling is soffited around structure (see diagram C). The combination of unit depth and ceiling height could be ideal for loft style studios with interior sleeping areas.

An intriguing possibility for the financing of such conversions might be the pursuit of historic tax credits. Threshold age eligibility for tax credits is 50 years. Beyond that, state and federal reviewers would have to be persuaded that the candidate tower is historically significant, but if obtained, a federal tax credit of 20% of the cost of construction would transform many office to residential development proformas.

The real obstacle to office to residential conversion may not be design or the costs of conversion. It may be in the way office rents are charged compared with the way residential rents are charged. Residential rents are based on assumptions of rents per square foot within the apartment itself. Office tenants are charged not only for the square footage within their space, but also for a portion of all the common areas supporting it, which may be a 20% or 30% premium to their demised suite. This means, of course, that the development proforma takes a 20% or 30% discount on the revenue-generating square footage. It’s an unattractive exchange.

However, as tenant leases turn over and tenants decline to renew or renew for less space, and as landlords face commercial loan resets at higher interest rates, landlords and their lenders may not have any other option.